Thursday, December 15, 2005

Thursday, December 08, 2005

My Kind of Church - the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

The Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. A gleaming wonder of white walls. Wide, open plan rooms. A string quartet softly playing in one wing, a flute concet in another and at some point, the lilting strains of a soprano. There is something utterly calm and peaceful about an art gallery; people taking time out of their busy lives just to sit and look at the paintings. The paintings in the Gemäldegalerie stretch from the Medieval era through to the 18th Century, leaving the 19th Century and beyond for the Neue Nationalgalerie next door. The Medieval paintings, from the dark ages of the last millenia, mostly depict grim religious scenes or two dimensional faces leafed in gold, but the real gems in the collection appear after the Middle Ages, and especially in the Dutch paintings at the back of the gallery. The collection includes a plethora of famous artists: works by Dürer, Titian, Vermeer, Velasquez, Canaletto, Gainsborough and Rembrandt gaze at us from the walls, so recognisable and yet such a shock in reality. I always feel moved when I see great art, and especially famous art. The the faces which have felt so familiar, and the compositions which are lodged somewhere deep in our consciousnesses greet us like old friends, at the same time as they shock us afresh with their mastery. The paintings really speak to me. The eyes of Dürer's old man look questioningly, suspiciously towards me; Susanna (below) is embarrassed to be caught getting out of the bath, but also flirtatiously proud of her gleaming, naked body, and the couple in Vermeer's masterpiece (above left) carry on their modest courting blissfully oblivious to the myriad eyes boring down on them from the gallery floor. It is strangely moving to recognise the inescapable humanity of these characters. The artists did not just paint from models or puppets, but from life. We see the emotion of the characters and recognise it as the same we possess. As I wander around the gallery, I recognise more and more that people have been the same since time began. Although we are separated by hundreds of years, I am being given the privilege of staring into the emotional lives of the subjects of these paintings.

The Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. A gleaming wonder of white walls. Wide, open plan rooms. A string quartet softly playing in one wing, a flute concet in another and at some point, the lilting strains of a soprano. There is something utterly calm and peaceful about an art gallery; people taking time out of their busy lives just to sit and look at the paintings. The paintings in the Gemäldegalerie stretch from the Medieval era through to the 18th Century, leaving the 19th Century and beyond for the Neue Nationalgalerie next door. The Medieval paintings, from the dark ages of the last millenia, mostly depict grim religious scenes or two dimensional faces leafed in gold, but the real gems in the collection appear after the Middle Ages, and especially in the Dutch paintings at the back of the gallery. The collection includes a plethora of famous artists: works by Dürer, Titian, Vermeer, Velasquez, Canaletto, Gainsborough and Rembrandt gaze at us from the walls, so recognisable and yet such a shock in reality. I always feel moved when I see great art, and especially famous art. The the faces which have felt so familiar, and the compositions which are lodged somewhere deep in our consciousnesses greet us like old friends, at the same time as they shock us afresh with their mastery. The paintings really speak to me. The eyes of Dürer's old man look questioningly, suspiciously towards me; Susanna (below) is embarrassed to be caught getting out of the bath, but also flirtatiously proud of her gleaming, naked body, and the couple in Vermeer's masterpiece (above left) carry on their modest courting blissfully oblivious to the myriad eyes boring down on them from the gallery floor. It is strangely moving to recognise the inescapable humanity of these characters. The artists did not just paint from models or puppets, but from life. We see the emotion of the characters and recognise it as the same we possess. As I wander around the gallery, I recognise more and more that people have been the same since time began. Although we are separated by hundreds of years, I am being given the privilege of staring into the emotional lives of the subjects of these paintings.The gallery also brought home to the the genius of the artists we now consider to be "great" The paintings of Rembrandt glow with an inner light, his characters resonate with emotion and thought. We picked his paintings out of all those on the gallery walls, without knowing the artist. Vermeer's clean lines and the telling body language of his characters surpass all his imitators: when coupled with his unerring colour sense and his use of rich textiles his painting actually made me gasp when I saw it hanging. The Gemäldegalerie is perhaps the closest I will ever come to knowing what philosphers mean by the sublime: I felt inspired, a

wed by the acheivements of men, and moved by the realisation that man is unchanging throughout the centuries, strong and weak in equal measure. I also realised that for me, the art gallery is my church. I have no belief in God or the soul, I don't think my body will carry on after I die and I disagree strongly with the ethics of organised religion. Nevertheless, churches have always given me a feeling of peace. This may be becuase a church is a place where people come to be still and quiet, to reflect and to pause, just as an art gallery is. It may be becuase a church is usually a huge building, full of beautiful art and objects, just as an art gallery is. I also love the sense of history, of the years stretching back until we can see into the past, which I feel in art galleries just as much as churches. The gallery is open late on Thursday nights, and I think next Thursday I will relish wandering through the whitewashed rooms, alive with faces from history watching me out of the corners of their eyes.

wed by the acheivements of men, and moved by the realisation that man is unchanging throughout the centuries, strong and weak in equal measure. I also realised that for me, the art gallery is my church. I have no belief in God or the soul, I don't think my body will carry on after I die and I disagree strongly with the ethics of organised religion. Nevertheless, churches have always given me a feeling of peace. This may be becuase a church is a place where people come to be still and quiet, to reflect and to pause, just as an art gallery is. It may be becuase a church is usually a huge building, full of beautiful art and objects, just as an art gallery is. I also love the sense of history, of the years stretching back until we can see into the past, which I feel in art galleries just as much as churches. The gallery is open late on Thursday nights, and I think next Thursday I will relish wandering through the whitewashed rooms, alive with faces from history watching me out of the corners of their eyes.

Wednesday, December 07, 2005

Judging the Quick (and the Dead)

"Never judge a man until you've walked two moons in his moccasins" Native American Proverb

I have been thinking a lot lately about whether it is possible to make any kind of moral judgement about anyone. This is partly because Hen has been filling me in on the delights of genetics, which suggests that our characters are in part formed through our genes. It is also partly because I have been reading Rabbi Marc Gellman's column in Newsweek. This has led me to think a bit about God, heaven and hell, and the way in which God purportedly comes to judge the living and the dead and section us off into good and bad, lucky sheep and unfortunate goats. This has always seemed to me an unfortunate analogy: goats cannot help being goats, and in the same way, sheep are not really responsible for their innate sheepish nature. Goats are wild and free becuase they are made that way, and sheep follow a shepherd (or one another) because it is in their nature to do so.

It seems to me, that people are not really so different from these sheep and goats. Each person is a product of his genetic make-up, which he cannot change, a product of his upbringing and history (i.e. nurture), which he also cannot change, and a product of his circumstances, which are again usually beyond his control. These factors combine in many different ratios to produce a finished person with a certain character - a propensity for anger, a compassionate nature, or a tendency to give up easily, for example. In order to suggest that a person has any "free will" or ability to combat these influential factors, we need to posit a self-determined force, an individual spirit independent of nature, nurture and circumstance.

This is getting quite philosophical, so let me give an example. Take, for instance, a jobless man. His lack of a job may be put down to laziness. There are obviously many other reasons why he might be unemployed, but let's keep it simple for now. Why might he be lazy? Firstly, he might have laziness inbuilt in his genes- his father and grandfather were lazy, he has inherited their laziness. Is this his fault? Could he overcome it? Perhaps, if he was sufficiently taught by, for instance, his mother, how to overcome his laziness. If he didn't have a helpful mother, however, is this his fault? He could not change his upbringing but perhaps he could find a mentor elsewhere, in the form of a teacher or friend? This is down to chance or circumstance, and is again, not his fault.

Are we, then, never to be blamed for our actions? Is there not a spark of individuality in each of us which can be held responsible for everything which we choose to do? Can an angry man teach himself to be calmer, or a lazy man force himself to struggle out of his inertia? Perhaps, but if his ability to do this is not inbuilt into his genes or taught him at some stage in his life then where does it come from? From that inner voice which urges us to do better, the conscience which pushes us away from bad deeds and towards good ones? And is this not taught us at some point in life, through our parents or our teachers or the media? Is our access to these influences not also governed by luck?

I find these questions very difficult to answer, and the answer I always come to is the same: we are all products of chance, and our luck is assigned to us by fate, leaving us almost powerless to change it. This doesn't mean I will stop trying to be a better person, or that I will encourage people not to try to better themselves. It does mean, however, that at the end of the day, we are stuck with our genetically created, impressionable, bodies and our free will is limited, if not non existent.

I do not believe in a soul, but perhaps if I did, this would answer the problem - God's gift to us of free will allows us to create our own destiny. Even if this was my belief, however, I think i would find it a bit difficult to accept that I had total free will - when I couldn't help bursting into tears, for example, or saw a kid who lacked the self-control to be quiet in class because he had never been taught to listen. If God really sorts the sheep from the goats on the last day, I think this is grossly unfair. Since God knew exactly how each human being would turn out, he deliberately created some sheep and some goats; some bad and some good humans; and condemned the goats to hell before he even put them on earth.

I think the North American proverb is very apt - we can never judge another person until we have actually inhabited their mental space. If I had the same genetic makeup, upbringing and life as Hitler, who is to say I wouldn't do exactly the same as he did. And as God's own son told us,

It seems to me, that people are not really so different from these sheep and goats. Each person is a product of his genetic make-up, which he cannot change, a product of his upbringing and history (i.e. nurture), which he also cannot change, and a product of his circumstances, which are again usually beyond his control. These factors combine in many different ratios to produce a finished person with a certain character - a propensity for anger, a compassionate nature, or a tendency to give up easily, for example. In order to suggest that a person has any "free will" or ability to combat these influential factors, we need to posit a self-determined force, an individual spirit independent of nature, nurture and circumstance.

This is getting quite philosophical, so let me give an example. Take, for instance, a jobless man. His lack of a job may be put down to laziness. There are obviously many other reasons why he might be unemployed, but let's keep it simple for now. Why might he be lazy? Firstly, he might have laziness inbuilt in his genes- his father and grandfather were lazy, he has inherited their laziness. Is this his fault? Could he overcome it? Perhaps, if he was sufficiently taught by, for instance, his mother, how to overcome his laziness. If he didn't have a helpful mother, however, is this his fault? He could not change his upbringing but perhaps he could find a mentor elsewhere, in the form of a teacher or friend? This is down to chance or circumstance, and is again, not his fault.

Are we, then, never to be blamed for our actions? Is there not a spark of individuality in each of us which can be held responsible for everything which we choose to do? Can an angry man teach himself to be calmer, or a lazy man force himself to struggle out of his inertia? Perhaps, but if his ability to do this is not inbuilt into his genes or taught him at some stage in his life then where does it come from? From that inner voice which urges us to do better, the conscience which pushes us away from bad deeds and towards good ones? And is this not taught us at some point in life, through our parents or our teachers or the media? Is our access to these influences not also governed by luck?

I find these questions very difficult to answer, and the answer I always come to is the same: we are all products of chance, and our luck is assigned to us by fate, leaving us almost powerless to change it. This doesn't mean I will stop trying to be a better person, or that I will encourage people not to try to better themselves. It does mean, however, that at the end of the day, we are stuck with our genetically created, impressionable, bodies and our free will is limited, if not non existent.

I do not believe in a soul, but perhaps if I did, this would answer the problem - God's gift to us of free will allows us to create our own destiny. Even if this was my belief, however, I think i would find it a bit difficult to accept that I had total free will - when I couldn't help bursting into tears, for example, or saw a kid who lacked the self-control to be quiet in class because he had never been taught to listen. If God really sorts the sheep from the goats on the last day, I think this is grossly unfair. Since God knew exactly how each human being would turn out, he deliberately created some sheep and some goats; some bad and some good humans; and condemned the goats to hell before he even put them on earth.

I think the North American proverb is very apt - we can never judge another person until we have actually inhabited their mental space. If I had the same genetic makeup, upbringing and life as Hitler, who is to say I wouldn't do exactly the same as he did. And as God's own son told us,

first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother's eye

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

One cake too many??

Me: I've got fat, haven't I?

Hen: What particular part of your chubbiness are you referring to?

Way to make me feel better hunny.....

March of the Affectionate (but not spiritually aware) Penguins

Zrenneh on his post 'The March of the Penguins' discussed Rabbi Marc Gellman's article,'The March of the Loving Penguins'. In his article, Gellman debated the ability of penguins to love, and came to the conclusion that although penguins were able to exhibit animal lust and self-sacrifice, they could not actually fall in love. This post is an extension to Zrenneh's counter argument.

Rabbi Gellman's argument has one major flaw. In arguing that penguins cannot experience love, he fails to define the word 'love', hence making his claim impossible to support.

Love is clearly a very difficult concept to pin down to a single definition, but in order for language to be meaningful, a broad agreement on the meaning of the individual words needs to be reached. The Merriam Webster online dictionary gives many ,meanings for the word, but the primary definition of the verb 'to love' is:

1 a (1) : strong affection for another arising out of kinship or personal ties (maternal love for a child)

(2) : attraction based on sexual desire : affection and tenderness felt by lovers

(3) : affection based on admiration, benevolence, or common interests

In 'The March of the Penguins', the penguins demonstrate all three of these forms of love:

(1) Strong affection based on close personal ties: the mother for the child (evidenced by her selfless nurturing of it), the penguinfor its partner (evidenced by the penguins' cooperation and the personal depravation endured for one another's benefit).

(2) Attraction based on sexual desire: although we may argue that this is only instinctive animal lust, such instinctive animal lust accounts for a great many human sexual encounters and is a large part of the human, as well as the animal, genetic make-up.

(3) Affection based on common interests, i.e. that of looking after their child. The cooperation exhibited by the penguins could teach many modern parents the benefits of working towards a common goal in harmony rather than in conflict.

Rabbi Gellman's only attempt at justifying his rejection of the concept of penguin love is the following:

"Penguins don't plight their troth to one another for fish or no fish, for colder or really colder, for seas full of krill or seas full of leopard seals."What he appears to be suggesting here, is that love is not really love unless it is everlasting and able to surmount all obstacles. This is manifestly not the case, not only for penguins but also for humans. Literature has taught us that the greatest loves may only be temporary: Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary and Rhett Butler are proofs that it is just as easy to fall out of love as it is to fall in love. In addition, rising divorce rates in the Western world indicate just how many people declare their love to be everlasting, only to discover that it is not. Very few people suggest that this calls into question the validity of the emotion in the first place.

Perhaps Rabbi Gellman's real problem with the concept of penguins falling in love arises, not out of their lack of eternal committment to one another, but from their inability to love an abstract being, that is, God. As a Jew, Gellman focuses throughout his article on the unique ability of humankind to love. Perhaps it is this abstract, spiritual love which is lacking in penguins and leads Gellman to abandon altogether the notion of penguin love. Whatever Gellman's reasoning, it is clear that, although there are possibly several types of love which penguins probably do not experience, there are also many types (illustrated by the Merriam Webster definitions) which penguins do demonstrate. To say that 'The March of the Penguins' is a story about love is a fair summary. As Elizabeth Barrett Browning so neatly pointed out, there are many different ways to exhibit love, and the penguins on the icy wastelands of Antarctica certainly seem adept at exhibiting many of these.

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

Chef extraordinaire: honey mustard chicken with creme fraiche mashed potatoes

I have always loved food, and often dreamt about being a chef when I was younger - I still think it is something I would love to do. I have always dreamt about staring a catering business from home, creating beautiful gourmet meals for dinner parties and cocktail parties - canapés are such a delight to cook but so time consuming that they can only be made very infrequently, for a very special occasion.

During my time at University, I worked for a staffing organisation, waitressing at high profile events and experiencing the catering styles of many different catering companies. My favourite was Rhubarb Food Design , who inspired me in my catering ambitions with their stunning creations, exquisitely presented as works of art (hence the "design" in the title). Rhubarb's food wasn't overly pretentious, unnecessarily pretentious or ridiculously miniscule. On the contrary, the portions they served were large, the food wholesome and delicious, and often some of the dishes they served were just old favourites, presented in an unusual way. One of their specialities which I was particularly fond of sneakily sampling was "bowl food": this came into play at a canapé party held on a weekday evening, when tiny canapes would not satisfy the hunger of the overworked executives attending. It involved reasonably sized bowls filled with a meal in miniature; shepherd's pie, bangers and mash, fish and chips, cauliflower cheese; exquisitely presented and cooked and a big hit with all the guests.

This gave Henry and I the idea of starting a "real food restaurant", a place which cooked traditional or original simple, tasty, hearty snacks, in reassuringly large portions, and cooked to absolute perfection. We had a few ideas for the menu:

- Corned beef hash

- Shepherd's pie

- Tuna pasta bake

- Steak and chips

- Risotto (of the day?)

- Irish stew

To spur on our creativity, each week, it is either my turn or Henry's to come up with an original surprise meal. Henry's meal was grilled aubergine with feta cheese and grated carrot last week, which was superb, really delicious. I had problems being totally original with mine this week, but it was very tasty: here is the recipe! For two, you'll need:

- 2/3 carrots

- 1 courgette

- 2 chicken breasts

- Olive oil

- Two large teaspoons of wholegrain mustard

- A large dollop of clear honey (about as much honey as mustard)

- 6/7 potatoes (depending on how hungry you are!)

- 1 small pot creme fraiche

- Peel the potatoes, cut them into thin slices and set them to boil.

- Julienne the courgettes and carrots

- Heat up a generous amount of olive oil in a pan and chuck in the vegetables

- Fry these lightly

- Meanwhile, slice the chicken into strips

- Mix together the honey and mustard in a bowl and dunk the chicken in it; roll the chicken around in the mixture until thoroughly coated

- Heat up a little oil in a new pan and fry the chicken and all remaining sauce until fully cooked

- Drain and mash the potatoes with the créme fraiche and a little honey.

- Serve the mashed potato in a ring around the edge of the plate, with the chicken resting on the vegetables in the middle. Enjoy!

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

Snow

Berlin is covered with a thin sprinkling of snow, scattered over the compacted, frozen ground and crunchy, icy grass. I love the way the snow squeaks as you tread on it, I love the way it traces the outline of the trees, giving them a second silhouette, the purer negative of the dark branches, and I love the way it dissolves almost as soon as it is touched, like a butterfly caught in your hand. We have already witnessed many different types of snowfall - the flat, feathery flakes floating though the air, thick with the promise of settling and laced with an intricate network of ice; the tiny, powdery shiver of snow which looks like icing sugar pouring down through a sieve; the small flakes bashing against the window, propelled through the air by the wind so they look like a swarm of midges attacking; and the driving rain of snow which leaves you bitterly cold and drenched to the skin.

On Saturday we wandered through the Tiergarten, listening to the silence which comes when a blanket of snow muffles the earth. We threw snowballs at the frozen lake (and each other); we stomped around making big footprints and we watched the sun sink lower and lower in the sky and glow peacefully through the snowy trees. I was reminded of Gustav Fjaestad's calm, snowbound paintings, and also of my favourite poem ever: Snow by Louis MacNeice:

I think this is a most incredible poem - it conveys so much in such a short space. The silence and menacing beauty of a world covered in snow comes across in the first stanza, especially the way snow is always such a shock when you look out of the window. The colours of the pink roses and the white snow, followed in the second verse by the bright gold of the tangerine paints a vibrant picture, composed almost like an impressionist painting by someone like Cailbotte: bay window with snow and pink roses, tangerine, and then in the last verse, the roaring red gold of the fire.The room was suddenly rich and the great bay-window was

Spawning snow and pink roses against it

Soundlessly collateral and incompatible:

World is suddener than we fancy it.World is crazier and more of it than we think,

Incorrigibly plural. I peel and portion

A tangerine and spit the pips and feel

The drunkenness of things being various.And the fire flames with a bubbling sound for world

Is more spiteful and gay than one supposes -

On the tongue on the eyes on the ears in the palms of one's

hands -

There is more than glass between the snow and the huge roses.

I love the idea of the 'drunkenness of things being various' - we are constantly bombarded by our senses until we are brimful of powerful impressions, and this is exactly what MacNiece intends to convey. He gives us the silence of the snow and the bubbling of the fire, the sight of the snow and the roses, the taste and smell of the tangerine and the toasty warmth of the fire. He draws these together in a list at the end of the poem, drawing our attention to the richness of our senses. In addition, with the word 'spiteful', he sets us slightly on edge - is the snow beautiful or malicious as well? The bubbling fire sounds like an alchemist, intent at his evil work, but it is not only spiteful but also gay. Is this another occasion of the intoxicating variety of the world, like the threatening beauty of the snow or the sinister yet comforting warmth of the fire? I have never fully understood the last line (any ideas?) but I will say that the final image of snow and huge roses, separated from the viewer by glass, finally frames the central image of the poem like a picture and allows us to watch the snow (and the "huge" roses) from the inside. We are sheltered from the snow, but we are not protected from the spiteful, gay fire.

Friday, November 25, 2005

Gissing - a neglected genius

George Gissing: A man I had never heard of until I started my English degree. And now a man whose genius I will be announcing to anyone who will listen. Everyone has heard of Dickens, Thackeray, Hardy, but Gissing remains well known only to the elect few. In my opinion his novels are far more fascinating than those written by the "greats" of Victorian literature. Unlike many of the others, Gissing's novels have the ring of truth, and seem like voyeuristic glimpses into the painful, private lives of their characters.

Gissing had a fascinating life, and he clearly drew a lot of inspiration from reality. Born in 1857, his family were never rich but he received a good education, promptly interrupted when he was caught stealing money to give to a prostitute, Nell Harrison, with whom he had become totally infatuated. After a month's imprisonment, Gissing was exiled to America, and returned several years later, desperately poor and friendless. He married Nell Harrison, but it was not a happy union - Nell was a drunkard and often returned to prostitution. Gissing eventually paid her to live apart from him.His first novel was a complete flop, although it was largely biographical, telling of his marital strife and discussing the lives of the most desperate levels of poverty in London's slums. Nell eventually died of poverty and venereal disease in 1888, and he married his second wife, Edith Underwood, not long after. This was even more disastrous than his first marriage - Edith became mentally unstable and violent, and had to be committed to an asylum (I always wonder, when biographies say something of this sort, whether the woman was really mad or just miserable, stunted and lonely, but time has erased these truths). Eventually he formed a union with Gabrielle Fleury, a young French translator, and he went to live with her and her mother in Paris, leaving his wife under the supervision of relatives. He eventually died of emphysema in 1903, aged only 46, having spent a vast part of his life in poverty and misery at home.

To me the genius of Gissing's writing is his ability to see inside the hearts of all his characters, high or low, rich or poor, he appears to have that incredible ability to empathise with everyone and anyone which is so rare for an author. The plot of his most widely read novel today, "New Grub Street", is in parts very similar to that of George Eliot's "Middlemarch" : poor husband, rich wife, wife inconsiderate and whinging, marriage fails. But the story of Amy and Reardon is far more beautifully rendered in "New Grub Street" than that of Rosamund and Lydgate in "Middlemarch", because Gissing understands the character of Amy to the extent where we understand her behaviour, and see the fragility of good intentions in a world of adversity. In short, Gissing's empathy enables us to sympathise with all his characters, and consequently makes us believe in his story to the point where it is hard to believe it is any longer a story. We have a sneaking suspicion that we may not have acted so very differently if the situation had been ours.

To give you a taste of this, I have copied a part of Chapter XXIV, Part IV of "New Grub Street", the most convincing part of the book in my opinion:

Both had come to this meeting prepared for a renewal of amity, but in these first few moments each was so disagreeably impressed by the look and language of the other that a revulsion of feeling undid all the more hopeful effects of their long severance. On entering, Amy had meant to offer her hand, but the unexpected meanness of Reardon's aspect shocked and restrained her. All but every woman would have experienced that shrinking from the livery of poverty. Amy had but to reflect, and she understood that her husband could in no wise help this shabbiness; when he parted from her his wardrobe was already in a long-suffering condition, and how was he to have purchased new garments since then? None the less such attire degraded him in her eyes; it symbolised the melancholy decline which he had suffered intellectually. On Reardon his wife's elegance had the same repellent effect, though this would not have been the case but for the expression of her countenance. Had it been possible for them to remain together during the first five minutes without exchange of words, sympathies might have prevailed on both sides; the first speech uttered would most likely have harmonised with their gentler thoughts. But the mischief was done so speedily. New Grub Street, Chapter XXIV, Part IV

Gissing's book the Odd Women, is also well worth a read - a strange but wonderful story about women's rights during the Victorian era, discussing the "Odd Women", that is, those who remained single and hence were not part of a pair.

Gissing is an inspiring, moving author and I'm not sure quite why he has been so neglected as an author in the past, Now, I believe, he is enjoying something of a revival, and his works are beginning to be reprinted. So check him out! You will be surprised.

Thursday, November 24, 2005

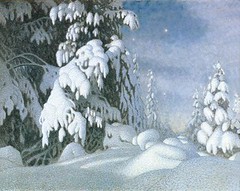

Gustav Fjaestad - a surprising discovery

I came across Gustav Fjaestad in the Brohan Museum, Berlin, a museum of art deco and art nouveau. In one room, all the walls had works by him, including an immense and spectacular tapestry which seemed so real I could feel the ice on my fingertips. I was totally stunned by his work, which seemed so beautiful and real and yet somehow magical, as if it inhabited a world untouched by human hands. I stood and stared for a long time, and went back to those paintings after I'd seen everything else. As usual, there were no postcards of the best pictures....

When I got home, I googled Mr Fjaestad, to find this passage about him on the Art Fund website:

To me there was no menace about the pictures - this was one of their key delights, that they felt entirely calm. (Perhaps this is one of the most interesting things about art, or the arts in general: the much room left for individual interpretation, the diversity of response and the unknown intentions of the creator.) To me the pictures spoke of perfect, untouched beauty. They reminded me of a visit to Esthwaite Water in the English Lake District, at twilight, when there was a light breeze rippling the lake like silk and the silver birches hung their heads ponderously over the water. The whole atmosphere was scented with the calm of evening, and I lay down on the quay to watch the fishing boats bob on the water and felt completely at peace. Probably if I did this on a day like the ones in Fjaestad's paintings, I'd freeze to the dock and would have to be cut out, planks still frozen to my back, but then nothing is quite how it looks in the picture...

Pictures from: www.mundofree.com, www.teosofiskakompaniet.net

When I got home, I googled Mr Fjaestad, to find this passage about him on the Art Fund website:

Gustav Fjaestad (1868-1948), made the frost- covered fields and snow-laden branches of the Swedish winter his hallmark. He too adopted country life, migrating to the densely forested province of Varmland in western Sweden, where he and his wife became the centre of a group of artists and craftsmen. But he was less interested in depicting country activities or wildlife than in exploiting the abstract pictorial qualities of the landscape. In his hands, the countryside in its winter guise became a vehicle for decorative surface patterns of dots and swirling Art Nouveau inspired arabesques. Yet they are never blandly pretty, and occasionally contain a hint of menace. The cold, unknown depths of the mysterious stretch of water contained within snowy river banks in Winter Evening by a River carry a sense of foreboding. Art Fund Magazine (author not credited)

To me there was no menace about the pictures - this was one of their key delights, that they felt entirely calm. (Perhaps this is one of the most interesting things about art, or the arts in general: the much room left for individual interpretation, the diversity of response and the unknown intentions of the creator.) To me the pictures spoke of perfect, untouched beauty. They reminded me of a visit to Esthwaite Water in the English Lake District, at twilight, when there was a light breeze rippling the lake like silk and the silver birches hung their heads ponderously over the water. The whole atmosphere was scented with the calm of evening, and I lay down on the quay to watch the fishing boats bob on the water and felt completely at peace. Probably if I did this on a day like the ones in Fjaestad's paintings, I'd freeze to the dock and would have to be cut out, planks still frozen to my back, but then nothing is quite how it looks in the picture...

Pictures from: www.mundofree.com, www.teosofiskakompaniet.net

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)